A City Within a City: The Forbidden City and its History

The Imperial Palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing, more commonly known as the Forbidden City, stands as a magnificent testament to China's imperial past. Constructed between 1406 and 1420, this architectural marvel served as the political and ceremonial center of the Chinese empire for over five centuries, witnessing the reigns of 14 Ming and 10 Qing emperors.

The Why and the When

The construction of the Forbidden City was ordered by Zhu Di, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty. His decision was driven by a complex interplay of political, symbolic, and practical considerations:

- Legitimizing Power: After usurping the throne from his nephew, Zhu Di sought to consolidate his rule and legitimize his claim to the Mandate of Heaven. Constructing a new imperial palace of unprecedented scale and grandeur served as a powerful symbol of his authority.

- Shifting the Center: Moving the capital from Nanjing to Beijing, his power base in the north, was a strategic move to better defend the empire against Mongol threats from the steppes. The Forbidden City became the physical and symbolic heart of this new center of power.

- Cosmic Order: The design and layout of the Forbidden City were meticulously planned according to traditional Chinese cosmology and principles of Feng Shui. It was believed to embody cosmic harmony and order, reflecting the emperor's role as the "Son of Heaven."

A City Within Walls:

The Forbidden City's vast complex, encompassing 980 buildings and covering 180 acres, was much more than just a palace. It was a self-contained city within a city, housing not only the emperor and his family but also thousands of court officials, concubines, eunuchs, and servants.

The Forbidden City's layout is rigidly symmetrical, with a central axis running from south to north, reflecting the hierarchical nature of imperial society. The most important buildings, including the Hall of Supreme Harmony, where emperors held court, were situated along this axis, increasing in grandeur as one approached the north.

A Legacy in Wood and Stone:

Built primarily of wood, with elaborate bracketing systems supporting its sweeping roofs covered in golden glazed tiles, the Forbidden City is a masterpiece of traditional Chinese architecture. Its red walls, symbolizing good fortune and prosperity, enclose a treasure trove of art, artifacts, and cultural relics, offering a captivating glimpse into the splendor and ceremony of imperial China.

Forbidden No More:

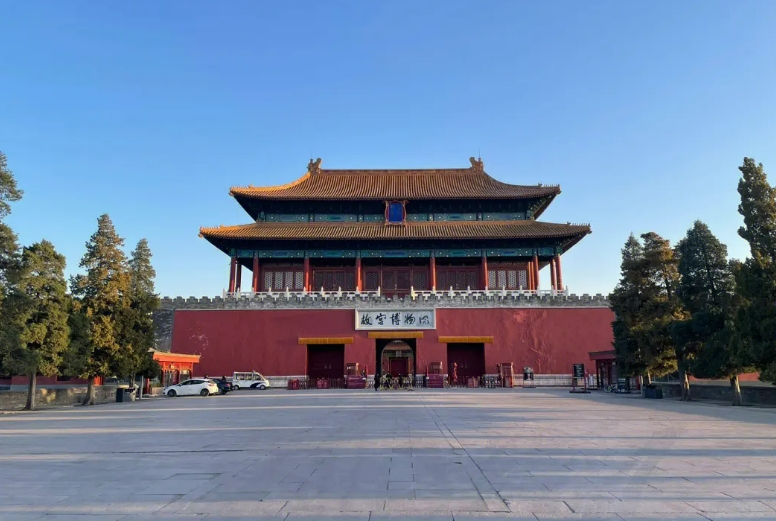

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the Forbidden City ceased to be the seat of imperial power. In 1925, it was transformed into the Palace Museum, open to the public for the first time. Today, it stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting millions of visitors each year who come to marvel at its architectural grandeur and immerse themselves in the rich history of China's imperial past.

Q&A:

1. Why was the Forbidden City called "forbidden"?

The name "Forbidden City" is a translation of the Chinese name "Zijincheng," which literally means "Purple Forbidden City." The "purple" referred to the North Star, believed to be the residence of the Celestial Emperor in Chinese astronomy, symbolizing the emperor's heavenly mandate. "Forbidden" alluded to the strict restrictions imposed on entry; only those with special permission from the emperor could enter.

2. What is the significance of the color red in the Forbidden City?

The dominant color of the Forbidden City is red, which held significant cultural and symbolic meaning in ancient China. Red represented good fortune, happiness, prosperity, and was associated with the Yang principle in Chinese cosmology, symbolizing masculinity and power. It was considered an auspicious color befitting the emperor's status.

3. How long did it take to build the Forbidden City?

The construction of the Forbidden City was a massive undertaking that spanned 14 years, from 1406 to 1420. It involved the labor of over a million workers, including skilled artisans, laborers, and conscripted peasants, who transported enormous quantities of materials from all over the empire.